You will like my offer

In the abundance of information around us, recommender systems (RSes) are becoming increasingly valuable tools. We use recommender systems every day in our lives. Many real-world applications, from e-commerce platforms like eBay to social media networks like Facebook and music streaming services like Spotify, rely on these systems. For example, it’s hard to find someone who hasn’t used Google Search.

At its core, Google is a search engine, but it does much more than just searching for information on the Web. Google analyzes user preferences and context, such as the user’s location to suggest nearby places or the languages they speak. The company employs similar approaches in other products, such as YouTube, Google News, and Google Ads. Notable, in October 2006, another pioneer in the space, offered a $1 million prize to anyone who could improve their recommendation algorithm.

Netflix time

An excellent example of a recommendation system is Netflix’s recommendation engine, which is one of the core features of the platform. This engine helps users spend more time enjoying content rather than browsing and searching, which, in turn, increases subscriptions and profits for the company. The system made suggestions based on factors such us the user’s viewing history, ratings, the behavior of other members with similar preferences, and information about the titles (e.g., genre, categories, actors).

When a new Netflix account is created, the system initially lacks information about the user’s activity to provide personalized suggestions. Therefore, users are prompted to select a few titles they like. This step is optional, and if skipped, the system bases its first recommendations on popular and diverse titles. As users engage with the platform, the system adjust its recommendations to be more personilized, with a bias towards recent activity.

How to select?

Recommendation systems use two primary approaches: content-based filtering and collaborative filtering. Some systems are hybrid recommender systems that utilize both methods.

Content-based filtering

Systems employing content-based filtering recommend items based on their features and relevance to a user’s query. The method also considers other items, making recommendations based on what user has liked previously. Some approaches explicitly use item content, such as in image or natural language processing applications, while others rely on descriptive features of items for matching and returning results.

Content based recommender systems (CBRSs) predict user preferences by comparing user profile and item profiles. Items are retrieved based on user-item interactions.

- User profile contains information describing the user, representing their preferences and behavior.

- Item profile represents an item’s attributes. It often consists of a collection of item features, typically represented as embeddings in a vector space. By calculating the proximity between vectors, content-based system determine similarity between items.

Collaborative filtering

Collaborative filtering (CF) groups users into distinct clusters based on their behavior. The system then recommends items to a target user based on the general characteristics of their group. The underlying idea is that similar users share similar interests.

This method relies on matrices that map user behavior for each item in system. Unlike content-based filtering, which calculates similarity between items, CF focuses on measuring similarity between users.

Collaborative filtering systems can be divided into two main types.

- Memory-based systems are extensions of k-nearest neighbors classifiers, predicting a target user’s behavior towards and item based on the behavior of similar users.

- Model-based systems employ predictive machine learning models, such as decision trees, Bayesian classifiers, and neural networks.

Context matters

Hybrid recommendation systems combine the strengths of both content-based and collaborative filtering methods. However, the input data for these systems can be further enriched. Beyond user-item matrices and embeddings, incorporating contextual information can significantly enhance recommendation performance.

For example, when a user searches for something, the system can consider not only the search query but also the device type and related results from previous searches. While browsing a movie title, the system might take into account not just the ratings left by the user, but also the time of day and how long they enjoyed a particular title.

Such systems, known as context-aware recommender systems (CARS), represent the next step in personalization and relevance for users.

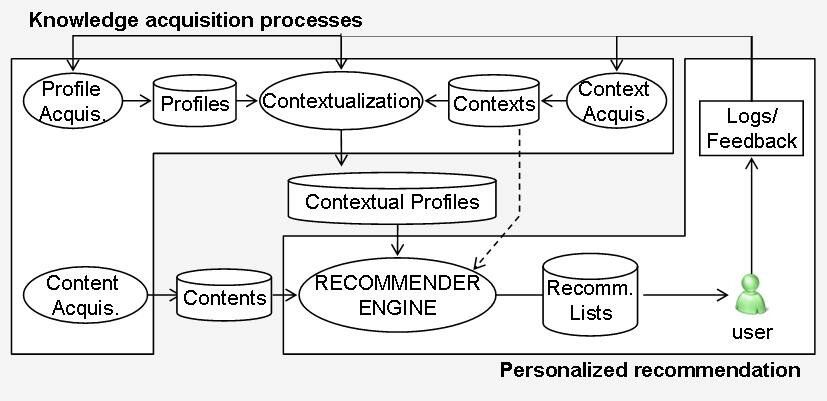

Source: Context-Aware Recommender Systems: a service oriented approach

The Architecture of context-aware RS comprises two main blocks:

- Knowledge acquisition processes. In this block, system getting knowledge about:

- user profiles (Profile acquisition), capturing user preferences and behaviors.

- item profiles (Content acquisition), collecting details about items, such as attributes and features.

- contextual attributes (Context acquisition), extracting distinctive contextual information, such as time, location, or device type, often from log files.

- Personalized recommendations. This block processes the outputs from the knowledge acquisition block to generate recommendation lists. It also logs user behavior to close the feedback loop, allowing the system to continuously improve its recommendations.

Deep learning CARS

Let’s explore model-based approach for RS in more detail. As mentioned earlier, model-based CARS often utilize neural networks for prediction tasks.

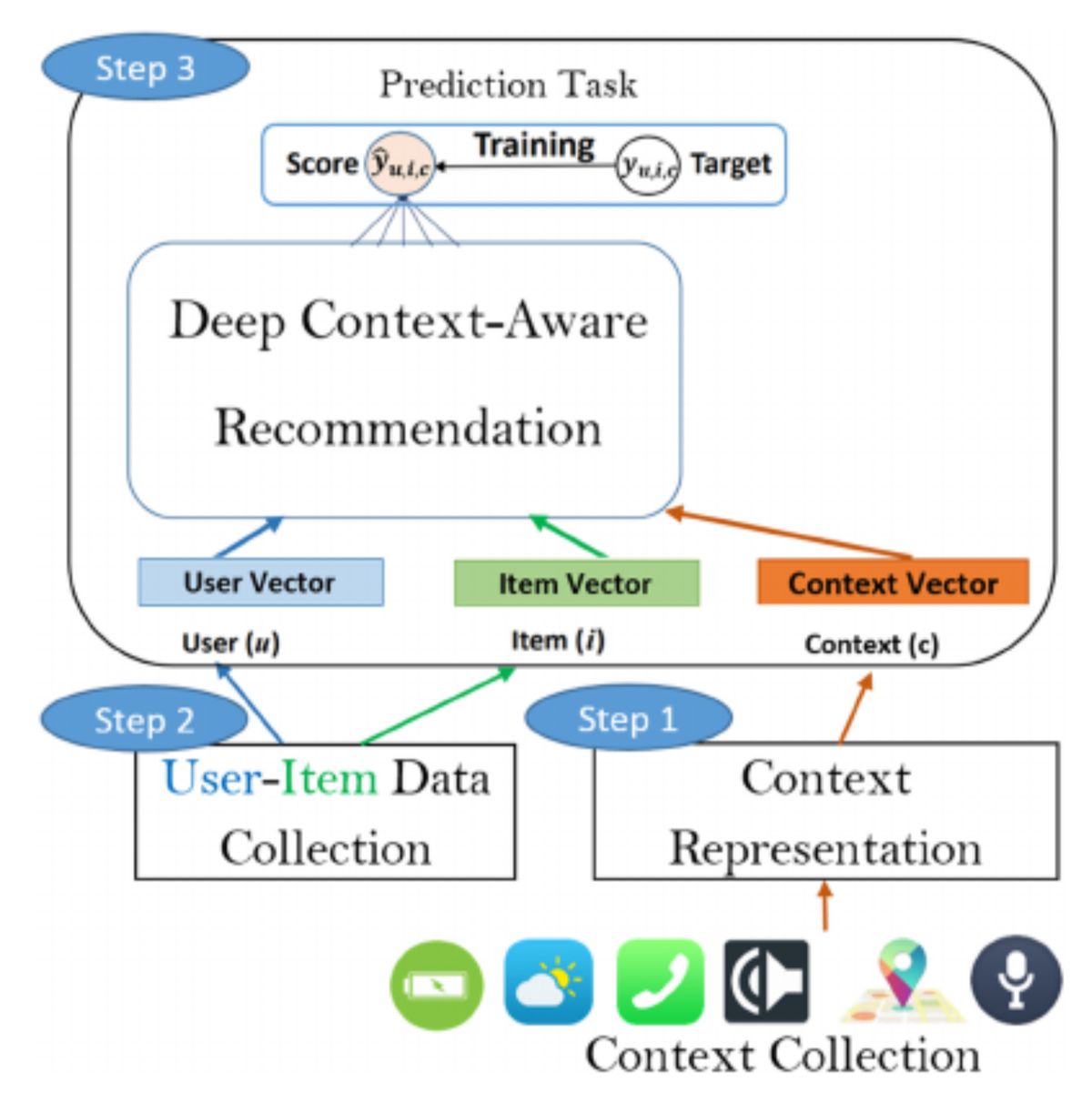

The authors of Context-Aware Recommendations Based on Deep Learning Frameworks proposed a deep learning (DL) recommendation framework, as illustrated in Figure 2. This framework includes key CARS elements, with blocks dedicated to user, item and context knowledge.

A notable feature of this framework is the integration of a neural network within the recommendation engine. This neural network enables the system to leverage complex patterns in user, item, and context data, improving the accuracy and personalization of the recommendations.

Source: Context-Aware Recommendations Based on Deep Learning Frameworks

Depending on the task, RS model can be trained for various objectives, such as: rating prediction, generating top-N recommendations and classification of user feedback. Once the task is defined, developers must prepare input data for the model. Contextual information can be represented in three different ways:

- Explicit representation utilizes all available raw contextual features without transformation or abstraction.

- Latent unstructured representation is a compact representation with reduced dimensions, often extracted from models like the hidden layer of an Autoencoder (AE).

- Structured latent representation encoded contextual variables into a hierarchically organized latent space, where latent variables represent cluster IDs derived from the data.

Users and items are typically represented as one-hot vectors. After preparing the input data, developers can select a CF recommendation model that integrates user, item and context representations.

For example, a multilayer perceptron (MLP) can be used to provide flexibility and nonlinearity, enabling the model to learn interactions between user, item and contextual vector representations. As an extension, the authors of Context-Aware Recommendations Based on Deep Learning Frameworks suggest using generalized matrix factorization (GMF), which leverages embedding of one-hot vectors for users and items. The linearity of GMF and the non-linearity of MLP can then be combined into a neural matrix factorizations (NeuMF) layer.

Improving performance

Despite the variety of approaches to building recommender system, optimizing performance remains a constant challenge.

One way to improve performance is through feedback loops. In a feedback loop, the output of the recommendation system is used as input to retrain the model. For example. the output of a movie recommendation system can be rated by users (e.g. skipped or watched), and this is then used to refine the recommendation model, improving its quality.

To measure and validate performance improvements, A/b testing can be employed. In A/B testing, two system versions are compared to determine which performs better. Users are randomly split between two variants, and statistical analysis is used to identify the superior version.

Privacy issues

While explicit contextual data can improve the performance of CARSs, it may also raise privacy concerns. With the growing prevalence of Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices like fitness trackers or self-driving cars, the application gave access to more user data than many expect.

Even without advanced IoT devices, modern smartphones come equipped with powerful embedded sensors, such as GPS, accelerometers, gyroscopes, digital compasses, microphones, and cameras. Developers of CARSs bear significant responsibility when using this data. Users, too, should remain vigilant, understand the consequences of potential data leaks or misuses. Users should review the permissions requested by applications or chose applications that process data locally, reducing reliance on remote servers

Conclusion

Recommender systems address a wide range of tasks but also introduce significant challenges. Preparing data, such as items, users and contextual information, is a crucial step. Model training requires iterative evaluation to refine predictions, as desired results are not always known in advance. Finally, continuous monitoring and updating of the recommendation engine are essential to maintain relevance and effectiveness.

Sources

- Why your Google Search results might differ from other people

- Netflix recommendations

- What is content-based filtering?

- What is collaborative filtering?

- Researchers Solve Netflix Challenge, Win $1 Million Prize

- Context-Aware Recommender Systems: a service oriented approach

- Context-Aware Recommendations Based on Deep Learning Frameworks

- Neural Collaborative Filtering